It became clear on Day2 of the ASPE PMP Boot Camp that the PMI world revolves around page 43 of the PMBOK. Just as I suspected.

If you’re still reading, you may be following my personal experiences of the ASPE PMP Boot Camp class in Denver, Colorado. I’m taking the training course for the purposes of sitting the PMI PMP exam, but I’m also sharing my thoughts along the way. Hopefully, this will help others who journey down this road. Just exactly what does this course cover? How much does it cost? What requirements does it expect of the students? And how will you personally feel when going through it? Those are the topics explored in this series. This is Day 2, so scroll down for earlier posts to catch the dialogue.

So… back to my premise… PMBOK page 43 is King! What’s on page 43 again? Page 43 of the PMBOK is the grid of Project Management Process Groups and Knowledge Areas. In other words, the processes that PMI project managers use to initiate, plan, execute, monitor, control, and close a project. When taking this PMP Boot Camp seminar, you will spend all four days examining page 43 from a hundred different angles, yeah a thousand angles. Everything you study comes back to it, so make sure you study it well. Memorize it early. Forward and backward. Be able to write it out upon demand. In fact, you are allowed to do just that within the first ten minutes of the PMP exam to use as a cheat sheet.

The ASPE instructor handed out 50 flash cards, which I found very handy for quick study. You’ll use them to name the 42 PMI processes, each having inputs, outputs, tools, and techniques. You must memorize every word of this or risk exam failure. And don’t try to write these out during class because you’ll miss too much of the lecture. Do it the night before. Unfortunately, understanding the general flow of processes is not enough for success. There are simply too many unfamiliar terms to mentally juggle. You’ll have to memorize too.

Make no mistake about it, this class is a Boot Camp just like its name says. Marine Corps Boot Camp. As I stated in my Day 1 post, this is very, very intense. The 42 PMI processes are just the beginning. As I said earlier, each one has inputs, outputs, tools, and techniques you must understand and memorize. But it doesn’t end there! Each one of those has a tidy list of 2 – 10 items encapsulated within: project documents, breakdowns, formulas, methods, theories, plans, etc. Want to count the cost? Multiply processes times your list of inputs, outputs, tools, and techniques, and again times those encapsulated lists and you’ve got thousands of pieces of information at your fingertips. You’ll literally be hit with scores each day. And you’ll be expected to recall them from memory for the exam.

This course will tax every resource you can muster, most notably: time. Don’t expect to have any kind of real life for these four days. Remember, this is Boot Camp not play time!

Okay, that’s probably enough about the hardships. Further posts likely won’t even mention that aspect unless I suffer a complete nervous breakdown and am dying to tell you about it. Instead, I’ll focus on other aspects of the course. But I wanted you to get the full picture of what you might experience in taking this course. It’s a doozie!

Are the hardships worth it? Of course! Gosh, it’s only four days. Anyone can survive that. So don’t let this discourage you. Sure it’s hard but survivable. Just remember, anything worthwhile is hard, or at least seems that way when you’re in the middle of it. Later, you’ll look back and realize it wasn’t all that bad. So stick with it and you’ll be glad you did!

You should also know that the Boot Camp course it not the end of your journey to the PMP exam. After this four days of classroom instruction, you should expect to 2-3 weeks in the ASPE Study Guide and PMBOK. Make sure to factor that into your near-term plans.

Plan to love the PMI methodology, at least for the duration of this undertaking. I mean love it! Dig in like a toothless redneck at a pie eating contest. Focus all your attentions on the PMI way of doing things. There’s a reason I say this; it’s a subtle but important one… If you get the notion in your head that this methodology doesn’t work for you, or can’t be justified in real life, or won’t work for your company, or any other reason to hate it, you will not have the fortitude to continue. You must (at least temporarily) set aside your personal beliefs and love this PMI approach like it’s you own. Imagine yourself as a highly paid PMI project manager at the top of a Fortune 100 company, or whatever it takes. Just love this stuff for a season.

During all this, I have gotten a renewed respect I got for the ASPE instructor, Dave Caccamo. Not only did he write the 850 page Participant Manual and Slide Guide, but delivers it with flawless execution. That’s no trivial occupation. Pray you get this guy. Seriously. He’s good.

Okay, that’s it for today. I’ve got 20 flash cards to write up, 43 processes to memorize, and five formulas to refresh my memory on. I hope you’re enjoying the series. Click the “About” page link to let me know what you think!

My Notes From Day 2:

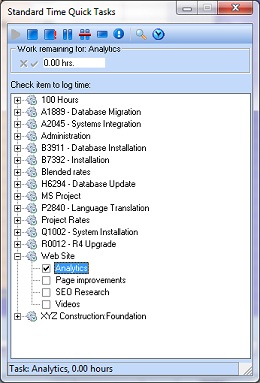

Start right out writing out the Project Management Process Groups and Knowledge Areas Mapping matrix on page 43 of PMBOK. Write out matrix in shorthand and put X’s where there is a process. 9 x 5 grid, 26 processes.

Flash cards came in real handy because we went over all the planning processes. Inputs and outputs were on the cards, and very handy to refer to in class. Write these out the night before! If you don’t, you can get lost in the pace. There are 42 processes. Must know all inputs and outputs. Instructor spends most time on Day 2 explaining inputs and outputs.

But flash cards only cover some of what you’ll cover. There are deep discussions of tools and techniques that are not on the cards. Much of that has to be studied and memorized as well.

Inputs and outputs of processes are so numerous and unfamiliar that memorization seems like the only way to get them. They are natural and logical, but just too numerous to mentally juggle. That means a huge amount of study.

Memorization is destroyed by adrenalin

There were a fair number of descriptions of the sneaky ways PMP questions can be posed. PMI will sneak in adjacent inputs or tools and techniques to trick you into a wrong answer.

There were several discussions amongst students about when they could take the PMP exam. Wait too long and forget everything. Try to take it too soon and risk not studying enough. Plus, there’s work and personal schedules to account for. Bottom line: this is a big commitment with a fair amount of risk.

Quick recall is the premium skill for this course.

Links to previous ASPE PMP Boot Camp posts

Disclaimer: The thoughts and feedback for the ASPE PMP Certification Exam Boot Camp associated with this series of posts are my own. In exchange for providing my feedback on this community forum, ASPE has provided benefits related to my course attendance.